History of Watermill Farm

Louw Rabie

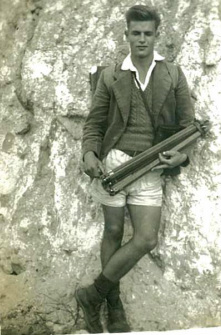

The most illustrious of the former owners here, was Louw Rabie (20/6/1922 - 16/12/2002) , brother of the ‘sestiger’ writer Jan Rabie. He started studying geology at the age of 16 at Stellenbosch University (inset photo) and became a legendary geologist, physicist, philosopher and poet. Watermill Farm (then simply known as Boplaas, which included the neighbouring settlements), was the only property he ever owned, purchased when he was in his sixties.

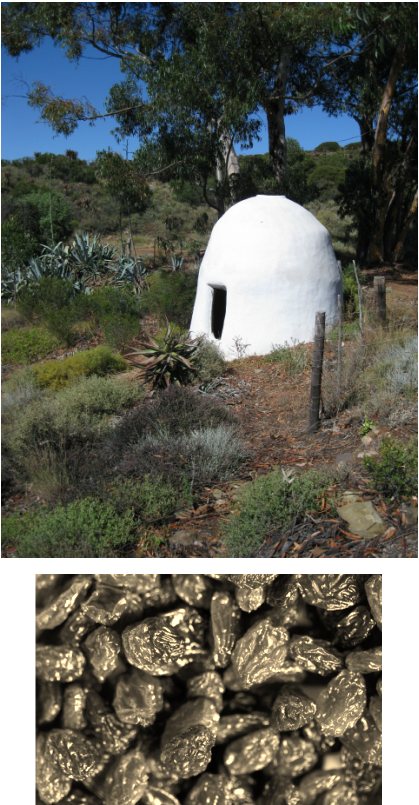

He was a man who had spent most of his life in nature, and was content to allow the buildings around him to simply melt back into the earth they were crafted from. The people of the Eastern Cape called him ‘The Man who Eats Stones’, from his habit of licking a rock to determine its composition.

At the age of 23 he wrote:" On reading a certain page in Spengler's "Decline of the West" (Vol !, p. 25) I suddenly realised why above all the other branches of the subject, practical structural geology has attracted my intention, namely because I like to concern myself with the part of geology which treats its subject matter as "becoming" and not simply as "become" in Spengler's sense - a geological structure is becoming, and a certain stage in its development is only a momentary position in an endless mutational sequence."

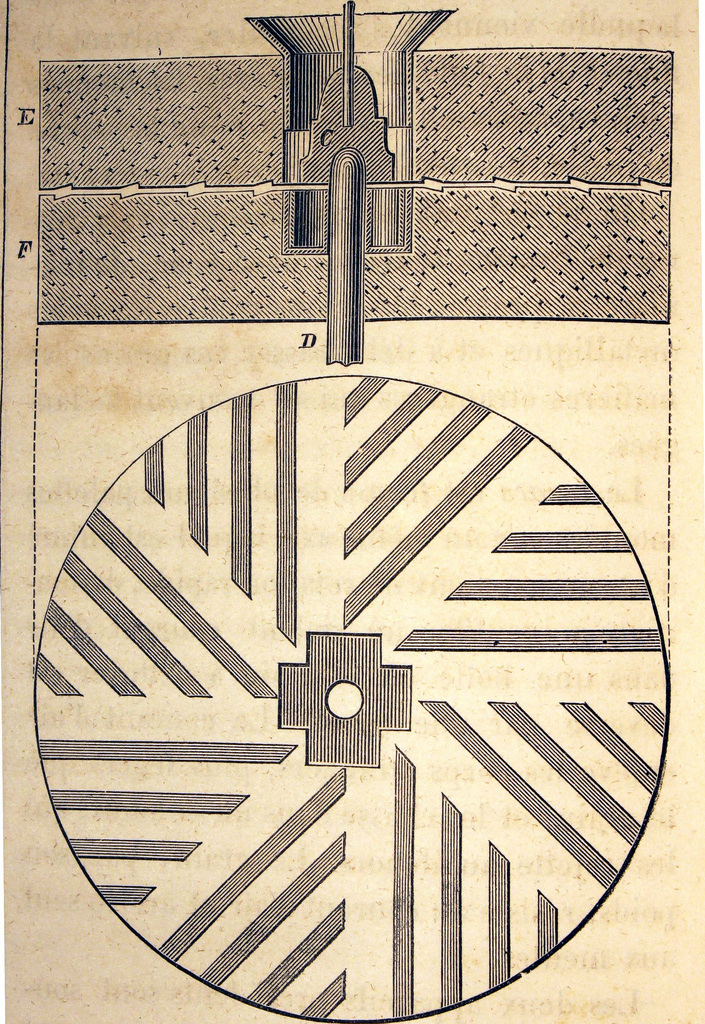

South Africa became an important antimony producer (Consolidated Murchison mine), mainly due to his meticulous mapping and interpretation of the mineralization in the structurally complex host rocks. (facebook.com/pages/Spilpunt-Information-for-geologists-exploring-Africa)

Stories of Louw abound, and a favourite was the story of his buying a new vehicle. Louw was a shy man and a recluse, and drove to Oudshoorn (some say Albertinia) (some 160kms away) to buy a new vehicle on his own. Once he had got the new vehicle, he drove it back for 10kms, then stopped, walked back to the showroom, picked up his old vehicle and drove for 20kms. He then stopped, and walked back to his new vehicle, and drove it along for another 20kms. He then repeated the process until he had got both vehicles home to the farm.

He was a man who had spent most of his life in nature, and was content to allow the buildings around him to simply melt back into the earth they were crafted from. The people of the Eastern Cape called him ‘The Man who Eats Stones’, from his habit of licking a rock to determine its composition.

At the age of 23 he wrote:" On reading a certain page in Spengler's "Decline of the West" (Vol !, p. 25) I suddenly realised why above all the other branches of the subject, practical structural geology has attracted my intention, namely because I like to concern myself with the part of geology which treats its subject matter as "becoming" and not simply as "become" in Spengler's sense - a geological structure is becoming, and a certain stage in its development is only a momentary position in an endless mutational sequence."

South Africa became an important antimony producer (Consolidated Murchison mine), mainly due to his meticulous mapping and interpretation of the mineralization in the structurally complex host rocks. (facebook.com/pages/Spilpunt-Information-for-geologists-exploring-Africa)

Stories of Louw abound, and a favourite was the story of his buying a new vehicle. Louw was a shy man and a recluse, and drove to Oudshoorn (some say Albertinia) (some 160kms away) to buy a new vehicle on his own. Once he had got the new vehicle, he drove it back for 10kms, then stopped, walked back to the showroom, picked up his old vehicle and drove for 20kms. He then stopped, and walked back to his new vehicle, and drove it along for another 20kms. He then repeated the process until he had got both vehicles home to the farm.